Introduction

The title of this report stems from an exhibition I saw at Gimple Fils Gallery in London called Wood for the Trees and Falling Leaves that showed the works of thirteen contemporary artists who for various reasons depict or reference trees in painting, sculptures and video. My aim has been to research this topic in greater depth to find out why certain people feel so strongly about trees and forests and what meaning they attached to them symbolically or metaphorically and why. Trees enchant people and their symbolic use transcends many cultures while at the same time pointing to individual cultural differences. In anthropology there are many detailed examples from around the world where trees are used as symbols in rituals marking birth, marriage, death in initiation rites, land ownership, individual or group identity and as a sense of place. Studies have been made of how forests, trees and their products are entwined into the social fabric of most societies (Turner 1967, Rival 1998, Gell 1995, Bloch 1998, 2005), such studies being used not only within anthropology but also for environmental and ecological concerns as well (Seeland 1997).

In mythology and religion the tree has been a symbol of life. In Norse mythology, Odin created the first man from the Ash tree, in Greek mythology Adonis was born from the trunk of a Myrrh tree into which his mother had transformed herself, the Ibo of West Africa venerate the Iroko tree as it possesses a mans heart and to chop it down would be the same as taking a life. Buddha achieved enlightenment by meditating under the Banyan tree. Mohammed in his Night Journey discovered the Tuba tree, of rubies, sapphires and emeralds which was at the centre of the Islamic Paradise. In Judaism the Tree of Life is a metaphysical construct used to explain the structure of the universe and is represented by the menorah or seven-branched candle stick and in Christianity, God forbade Adam and Eve to eat from the tree of knowledge of good and evil while Jesus, son of a carpenter in this world, died on a wooden cross that became the symbol of Christianity. The examples can go on ad infinitum.

Artists also use and reference trees and forests in their work with many examples throughout history. Hohl (1999) explains that in the seventeenth century the landscape paintings of artists such as Claude Lorrain and Jacob van Ruisdeal showed how ‘splendid trees demonstrate the force of nature…..The paintings of both provide evidence of the fact that, to their painters, a tree is more than just a tree. It is a symbol of the comprehensiveness of divine creation, of which he, the individual, is a part, a particle’ (Hohl 1999:11). In the nineteenth century, after the Napoleonic wars, for the artists of the Romantic period such as Casper David Friedrich (1774-1840. fig. 1.), the tree became a representation of the artist’s spiritual consciousness, often representing the solitary individual who sublimely ‘longs for integration into an all encompassing whole’ (Hohl 1999:11). Can this be said of today’s artists who use trees in their work? Or are their works not about the trees they depict at all. For Cézanne, in the modern period, trees were servants to his composition and with Monet ‘all psychological and philosophical identification ceases. A tree is no longer a tree, but in its optical appearance here and now a painting process’ (Hohl 1999:16) where the painted surface is more greatly respected than the subject matter. Again the list of artists referencing trees in the early twentieth century is too long to recount in an essay of this length.

My aim therefore is to discuss some recent studies that focus on trees and forests by looking at writing of Laura Rival, Maurice Bloch and Alfred Gell. I will then enquire what trees mean to artists and viewers of their work when placed in exhibitions or other spaces as contemporary art. I will ask; how do Western contemporary artists perceive trees, are they just continuing the tradition of depicting an archetypal feature of ‘the landscape’ or are there other symbolic reasons for their use? Has contemporary art become so urbanized that artists wish to somehow recreate a nature that is becoming lost to them in a more technological and globalised world? Or are they being didactic and aiming to bring to light more sinister aspects of our contemporary society that often lay hidden? Does the use of tree imagery and metaphors set these artists apart as a group or do artists work independently from other artists and from their own culture? These are some of the questions I will raise.

Fig 1. Casper David Friedrich Oak Tree in the Snow 1829

Trees, forests and their products as theoretical concepts.

The study of indigenous knowledge of trees and forests and the meanings that are attached to them has interested writers of many disciplines. As Andrew Garner says, ‘Trees and forests have recently re-emerged as a focus of study using a variety of theoretical approaches’ (Garner 2004:87). He goes on to list these approaches as, historical, those influenced by structuralism, as symbolism. Also in phenomenology, theology, ecology, geography, environmental studies and anthropology. In Laura Rival’s social anthropological approach of theorising the interactions between human societies and their natural surroundings she aims to show that, ‘trees are used symbolically to make concrete and material the abstract notion of life, and that trees are ideal supports for such symbolic purpose precisely because their status as living organisms is ambiguous’ (Rival 1998:3). Rival quotes Durkheim who says that, ‘…“a collective sentiment can become conscious of itself only by being fixed upon some material object”..’(Rival 1998:2). But she then questions him because in material culture studies ‘anything material is treated as object-like’ whereas in her edition of essays, trees are theorised as living organisms and more like ‘natural symbols’ but the ambiguity of whether they are an object or a life-form arises as the category ‘tree’ is not a biological species that existed in the world before recognition and classification. Therefore ‘trees’ as a category, like ‘landscapes’, is essentially cultural and historical.

Rival discusses ‘the role on tree symbolism in life cycle rituals and community politics and that unlike others who have projected human attributes to non-human domains she claims that,

…what seems to drive tree symbolism is not so much the transfer of intentionality on to non-human living organisms, but, rather, the need to find within the natural environment the material manifestation of organic processes that can be recognised as similar to those characterising the human life cycle,

or the continued existence of social groups (Rival 1998:7).

Rival backs up her theory by giving many examples from other chapters in her edition such as Giambelli’s demonstration that each stage of the life cycle of coconut palm is used for the different life cycle rituals of the Nusa Penida, Bali (Rival 1998:133-157). Also she argues that trees and woods are linked to ‘life crisis’ rituals as well for example ‘a growing movement in parts of Europe to replace cemeteries and graves with ‘peace forests’…….the great advantage of trees over tombs is that only ashes and trees – if left undisturbed – last forever. Trees are true symbols of life and eternity; graves are symbols of death and fading memory’ (Rival 1998:9). She does not mention the growing lack of space in cemeteries today as a factor!

Rival also discusses the analogy made in different cultures between trees and the human body, either as a whole person or analogous to body parts such as bones to trunk, sap to blood, bark to skin, leaves to hair and branches to arms. More metaphorically trees have been used to represent genealogical connections in family trees, whole kinship groups, national identities and as political emblems or more abstractly as the self, the soul, the spirit or ones personality. Below I will show how the oak tree in Anya Gallaccio’s work has been associated with British identity.

Some of the authors in Rival’s edition discuss indigenous knowledge of forests compared to that in Western policies of regeneration and conservation and how ‘oblivious Westerners can be of the fact that the natural world is intricately entangled with human history, and that what we call forest today is, to a large extent a human construction’ (Rival 1998:15). Following these authors Rival aims to show that ‘tree symbols revolve around two essential qualities, vitality and self-regenerative power’ (Rival 1998:3). She says that in all cases, ‘trees appear to be potent symbols of vitality precisely because their status as living organisms is so uncertain. Life travels in them from seed to fruit to seed….without full individuation. Trees do not have a life, they propagate life’ (Rival 1998:23). And she continues to claim that due to trees being seemingly everlasting organisms they appear to transcend death as they are not alive, in the way that animals are, in the first place, and she questions how we should interpret the fact that they ‘physicalise’ the human wish for transcendence.

Rival criticises anthropologists who fail to link politico-economic analysis with the changing cultural meanings and symbolism today. She explains that by linking these Mauzé’s (1998) example (in her edition) shows that the Northwest Coast Indians are involved in ethnic and green politics and consequently their ‘cultures are changing from ‘wood-oriented’ to ‘tree-obsessed’’ (Rival 1998: 15). Rival concludes that only by linking these issues can we, ‘grasp the complex status of a culturally transformed tree, at once alive as any ancient tree and as object-like as a totem pole. And even more striking, these culturally modified trees are symbols of vitality, welfare and well-being in both traditional and modern belief systems’ (Rival 1998: 15). Rival also explains that arboreal imagery becomes central to the representation of political processes and socio-economic relations.

In Maurice Bloch’s essay ‘Why Trees Are Good To Think With’ he uses a cognitive approach to the meaning of life and discusses, like Rival, the ambiguous status of trees as living organisms. He argues that if trees are universal symbols of life, a cross-cultural analysis of tree symbolism has to begin with the local theories of life and death. But Bloch argues that the distinction between life and death is not clear-cut but graded, and always uncertain. Like Rival he claims that the symbolic power of trees is due to them being good substitutes for humans in a similar way that animals have been used but trees have not been the object of such scrutiny. He says perhaps this is because animals are seen as a more spectacular subject for ethnographic films. But he argues that trees are just as interesting and,

Their substitutability [as substitutes] is due to their being different, yet continuous with humans, in that they both share ‘life’. This distant commonality is intriguing, problematic and uncertain. Thus, both the shared element – life – and the uncertainty and distance between humans and trees must be considered and understood (Bloch 1998:40).

Bloch’s aim is to look for universal reasons why cognition of trees is particularly suitable for religious symbolism. He approaches this study by conceptualizing life itself and concludes that it is a graded affair, ‘plants are less alive than butterflies’ and animal rights protesters are ‘more concerned with cruelty toward sheep than spiders and rarely feel strongly about killing moulds’. And this graded picture of life, ‘suggest a possible explanation of the symbolic uses of plants and trees’ (Bloch 1998:34). He goes onto say that this is just one explanation awaiting others such as in ecology and history as he believes in interdisciplinary communication as ‘heuristic divisions threaten to gain a false reality ’(Bloch 2005:18).

Before turning to my research on use of trees in contemporary art I will first remain within anthropology, or rather anthropology of art, to discuss Alfred Gell’s (1998) theory of art because he too touches on the subject of trees as indexes with agency (which I will explain below). In his theory Gell viewed all art in terms of social relations ‘…that obtain in the neighbourhood of works of art, or indexes’ (Gell 1998:26), and these social relations he saw as the fundamental subject matter of anthropology. Having cast aside aesthetics he was instead interested in ‘art-like’ relations between persons and things. He claimed that a work of art is part of ones distributed person, meaning that people are present not just in their bodies but in everything around them. In Art and Agency (1998) Gell argued that art objects are material parts, or extensions of agency (or doing) of the artist or of those that utilize these works and therefore he endowed such artworks, or artefacts, with the status of honorary persons. These then have the ability to participate in social relationships, either actively or passively, with human beings or with each other. Nicholas Thomas (1998) explains that Gell considered art works as a ‘technology’ and as such were ‘…devices “for securing the acquiescence of individuals in the network of intentionalities in which they are enmeshed”’ (Thomas 1998:viii). In other words they were traps that catch the viewer and enchant. It is also crucial to his theory that artworks (or indexes) ‘display ‘a certain cognitive indecipherability’, that they tantalize, they frustrate the viewer unable to recognize at once ‘wholes and parts, continuity and discontinuity, synchrony and succession’..’ (Thomas 2001:5). Thomas says that Gell’s theme of captivation is important to many forms of cultural expression in diverse contexts.

Gell believed that ‘the anthropology of art should address the workings of art in general and that his work was addressed ‘to scholars in anthropology, rather than in the wider field of those engaged in art practices’ (Thomas 2001:3). Gell himself found the term ‘artwork’ troublesome and said ‘To discuss ‘works of art’ is to discuss entities which have been given a prior institutional definition as such’ (Gell 1998:12), and believed this to be the subject of the sociology of art ‘which deals with issues complimentary to the anthropology of art, but do not coincide with it…….these can only be discussed in terms of the parameters of art-theory’ (Gell 1998:12). So he abandons the term artwork and employs the term ‘index’ instead. But his use of indexes is not in the exact Piercean way, with a direct existential connection with its object, but his view of index ‘permits a particular cognitive operation which I identify as the abduction of agency’ (Gell 1998: 13). Therefore this is a broader meaning of indexes than that used by Pierce as abduction ‘covers the grey area where semiotic inferences (of meaning from signs) merge with hypothetical inferences of a non-semiotic (or not conventionally semiotic) kind’ (Gell 1998:14). Unlike Pierce, Rival and Bloch, Gell avoids the use of the notion of ‘symbolic meaning’ but places emphasis on ‘agency, intention, causation, result and transformation. I view art as a system of action, intended to change the world rather than encode symbolic propositions about it’ (Gell 1998:6) In his view this ‘action-centred approach’ to art is more anthropological rather than interpreting objects as if they were texts.

In Gell’s chapter, ‘The art nexus and the Index’, he describes how an index (or material thing) can have agency like a person and can dictate to the artist, rather than the other way round, and that the artist responds as a patient to the index’s inherent agency. He cites an example of an account written by Father Roman Pane, at the behest of Christopher Columbus, of the religion of the inhabitants of the Antilles. This Father,

…reported that: ‘Certain trees were believed to send for sorcerers, to whom they gave orders how to shape their trunks into idols, and these “cemu” being then installed into the temple-huts, received their prayers and inspired their priests and oracles’ …..Even this terse statement is enough to establish the possibility that, in certain instances, it is the agency in the material of the index, which is held to control the artist, who is the patient with respect to this transaction’ (Gell 1998:29)

Gell backs up this rather random example, from way back in the fifteenth century, with Turners account from 1967 of the Ndembu who carved figurines from the wood of the sacred Mukula tree for use in ‘rituals of affliction’ where they help women regain their fertility. Gell argues that the tree (or index) in its living form acts as agent (or person doing) and imposes form on the index in its subsequent, carved, state. Therefore creating an art-like relation between ‘things’. Gell then relates this to Michelangelo carved slaves being ‘liberated forms which inhere in the uncut stone or wood’ as if the material was dictating to the artist rather than the other way around. Also that the ready-mades ‘forced themselves’ on Duchamp, (as patient) ‘who responded to the appeal of their arbitrariness and anonymity’ (Gell 1998:30). In this example the artists does not make but ‘recognizes’ the ‘index which inherently possesses the characteristics which motivate its selection by the artist as an art object, to which none the less his name is attached as originator’ (Gell 1998:30). Can this be the case for the artists I will be describing below in relation to use of trees and tree imagery in their work?

Perceptions of the Tree in Contemporary Art

I do not intend to list all the artists or artworks representing trees that I have found during my research as the list would be far to long for an essay of this length. Instead I have included some illustrations (pp. 21 - 22) at the end of this paper and will only focus on three artist’s works in depth and relate these to the issues I have discussed above in the writings of Rival, Bloch and Gell. Today’s world has become increasingly fragmented and diffuse and probably people’s experience of ‘nature’, especially in metropolitan centres, has as well. Could this account for the fragmented presentation of trees in many works today rather than depicted as whole, as in Friedrich’s painting? (fig 1.). Responding to Modernism, artists such as Picasso, Mondrian, Léger, Klee (figs. 11-14 p.20) and others used fragmented images of trees in their work. Are we now entering a new Modernism and changes in our perception of nature? Or is it that the turn to installation art, land art and new media since the 1960s and 70s has enabled this shift to partial inference rather than mimetic depictions? Bruderlin (1999) quotes Adorno who said, ‘Nature reveals itself in its very abstraction, denaturalisation and asceticism, and not in the mimesis of the naturally beautiful or in idyllic allegories of conciliation’ (Bruderlin 1999:116). This echoes Gell who said (above) that art-works are technologies that trap and enchant by displaying a certain cognitive indecipherability. I shall now be guilty of discussing art-works in this report that have been given (as Gell said) a prior institutional definition as such, but will still try to relate them to the above discussion. Why do artists as a social group (or as individuals) reference trees? What does this say about their position in society?

Anya Gallaccio (b.Scotland 1963) exhibited several freshly felled oak trunks in the Duveen Galleries at Tate Britain in an exhibition named Beat (2002). These substantial fragments of trees with their bark left on but stripped of branches were placed between the Ionic columns of the gallery and intended to appear as monoliths or monuments (fig 2). To what though?

Fig 2. Anya Gallaccio Beat. 2002

What did the trees mean to the artist, the organizers and the public? Why these manipulated ready-mades or un-carved sculptures or installation? Is nature the agent and the artist the respondent? Did these trees force themselves on Gallaccio, in the way Gell explains the ready-mades did on Duchamp (p.7 above), did she choose or ‘recognize’ them? Or referring to Rival’s theory can we consider them culturally transformed and at once alive, as they had recently been felled, or object-like as British ‘totem poles’ (p.4 above)? Do they create relationships?

Gallaccio was commissioned by the Tate to make a work for this space so the large scale was obviously a factor in her decision to choose such trunks, and the sponsors, Malvern English Mineral Water, were ‘proud to be associated with a work that portrays the beauty and purity of nature’. They said the ‘marriage of nature and art forms the basis of a union that we hope will be enjoyed by all who experience Gallaccio’s work’ (sponser’s advertising 2002). To the Tate Britain director this piece engaged obliquely with landscape painting which, ‘resides as a dominant force’ displayed in the surrounding galleries housing five centuries of British art, and that ‘this above all prompted her to explore the possibilities of working with the archetypal symbol of both the national landscape and the nation itself – the oak tree’ (Deuchar 2002:5).

The oak tree has been seen as a powerful signifier of British heritage, history and its countryside and once, so the catalogue says, represented the economic core of the country as an indispensable material of imperial naval power in the eighteenth century and thus a precondition of accumulation of wealth that allowed the for Palladian buildings like Tate Britain. Such oaks, as old as this building, used to symbolize the strength of the British people and spoke of tradition and longevity but are now perhaps just grove of memory. Are these mutilated trees commenting on the bleaker side of colonialism? The blocks of sugar that accompanied the trunks in this exhibition could be seen to highlight the link between the Tate and the sugar industry, slavery and the slave ships made of oak. By looking at socio-economic aspects, as suggested by Rival in her work above, we can ‘grasp the complex status of a culturally transformed tree’ (Rival 1998: 15). Pointing to purity of nature for the sponsors, to the Tate’s landscape painting and British-ness for its director, maybe creating traps or enchanting the urban viewer who may wonder ‘why’ these ready-made trunks out of context – “ is it art?” By using these trees and naming them as ‘her work’, has the artists achieved a degree of ‘cognitive indecipherability’ as Gell says above (p.6) to entrap the viewer? - Maybe. Also can these trees be seen as a ‘system of action’ for changing the world in Gell’s sense or is their strength in ‘symbolic meaning’ in as in the view of Bloch and Rival. I think the later is more the case. In the catalogue Heidi Reitmaier claims that, the experience ‘for the viewer, [theoretically] is a conflation of the tangible, the real, the metaphorical and the personal’, and her work ‘seduces the viewer into believing everything, and then disbelieving at the same time’ (Reitmaier 2002:44).

Rather than focus on the tree trunks themselves perhaps I should look at the Gallaccio’s œuvre in the way that Gell’s examined Duchamp’s in his discussion of the distributed mind in the concluding chapter of Art and Agency. By looking at an artists œuvre we may discover the mind of the artist through the material manifestations of that mind (or indexes of her agency), and find the forth dimension (or creative energy) in this ‘three-dimensional land’ (Gell1998:243). I am not comparing the œuvre of this YBA in any way to Duchamps’ but just using Gell’s theory.

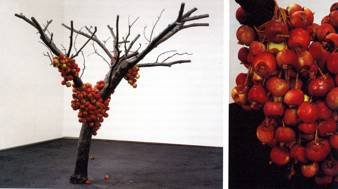

Most of Gallaccio’s sculptures and installations are temporal, as they change by decay, growth or disintegration as the materials she chooses to work with are ephemeral, unstable and impermanent and are often resistant to commodification. She questions the supposed division between ‘nature’ and ‘culture’ and shows the appropriation of nature for human consumption and is more interested in physical transformation and processes than in the material object per se. Like most artists she relates to her past practice in each piece as in, blessed (fig.3) and because nothing has changed (fig. 4) with their rotting apples these fruit trees connect the oak trees in the Tate with her earlier work composed of rotting flowers, preserve beauty (fig.5). She shows a graded picture of life, where the mould grows as the flowers or apples die which in Bloch’s view above may suggest a possible symbolic uses of plants and trees to the life cycle of humans. The oak trees are a link also to later work of a very small bronze twig resting on the gallery wall in the Gimpel Fils exhibition Wood for the Trees. This new work is a departure as it halts time (being bronze it cannot decompose) and can therefore be commodified.

Fig. 3. Anya Gallaccio. Blessed. 1999

Fig 4. Anya Gallacio Because Nothing Has Changed 2000

250 cast bronze apples

Fig 5. Anya Gallaccio Preserve ‘beauty’ 1991

800 gerbera (Beauty), glass

Too long to detail here these works of Gallaccio constitute a ‘complex web of personal, historical, mythic, economic, symbolic and social associations’ (Reitmaier 2002:38). She generally works site specifically with each context informing her work that are ‘a way of drawing together many possible meanings within a single response to place’ (Reitmaier 2002:38). She is concerned with natural systems and modes of knowledge associated with them. So as in Gell’s view I could say that ‘each artwork…is a place where agency ‘stops’ and assumes visible form’ Gell (1998:250). The oak trunks in the Tate are perhaps one of these stopping points where her consciousness surfaces and becomes the distributed object of her person. But unlike Duchamps work, many of Gallaccio’s will rot away alternatively, like Duchamp, she is ‘one particular person exercising one particular agency’ over a lifetime. What about a ‘collective of artists referencing trees’ as a ‘cultural tradition’ seen as a distributed object? Where trees are not just used as symbols but as vehicles of collective power of the artists to attract, subvert the given order and negotiate the contemporary art-world while also referencing a traditional motif. Or is it curators who bring groups together as in the Gimpel Fils exhibition (p.1 and images pp.17- 19) . In a commercial world is it they who have agency?

Ori Gersht (b. Isreal 1967) is an artist who uses tree imagery in some of his photographs and films. I have recently seen his powerful short film Forest 2005 (fig. 6) which was shot deep in the interior of the ancient pine forest of Moskovko in Eastern Europe, when local woodcutters (whom we don’t see) were at work. It consists of a sequence of slow panning shots across a band of the tree trunks (like Gallaccio’ oaks above, we only see part of the tree) in dappled sunlight and in complete silence. Then as the camera pans across the forest, individual trees sporadically fall and crash in slow motion to the forest floor. The camera does not respond to these movements but continues to pan, with the falling trees being viewed as if out of the corner of the eye. But as they begin to fall a tearing sound begins on the soundtrack, at first quietly and gradually amplified to a massive, crashing roar before silence resumes again and all is still and calm as the panning continues.

Fig 6. Ori Gersht Forest 2005 16mm film transfered to DVD

This film in its haunting beauty evokes the Romantic paintings of the past. German Romantic painters like Casper David Friedrich, cited above, ‘bestowed these ur-forests with a mystical, transcendent presence….investing their elemental beauty with enough of a frisson of untamed wildness to evoke a feeling of the sublime’ (Bode 2005:5). But more recently some of the appalling acts of genocide by the Nazis took place in these forests that Gersht explores and have meaning for him as his own father–in-law was born in eastern Europe and was one of the few survivors of the mass killing of 2,180 Jews there. This event, too horrific to try to represent without descending into abjection, can only be alluded to, like Romanticism’s lack of completion (as a state of becoming). In Gersht’s film, there is a sense of ‘ongoing movement [which] can be said to relate to the impossibility of finding a stable Absolute – whether it be redemption, or meaning’ (Millar 2005:16). Millar says this film infers an ongoing moral vigilance, in not forgetting those that perished with each falling tree but not lingering on them (as the camera pans away). This is not because of a lack of compassion but because the death, symbolically represented, provokes ‘fear and trembling’ in the artist whose has family connections here. The survivors of the atrocities are not true witnesses and can only represent the missing by guessing at the horrors. This brings to mind the philosophical conundrum of George (Bishop) Berkeley (1685-1753), ‘If a tree falls in the forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?’

This work could echo Bloch’s view in turning to the local theories of life and death of Gersht’s personal family history and of the Jewish population. Where life and death are not clear-cut because the memory of the dead lives on in those left behind. As in Bloch and Rival’s view the symbolic use of trees can be said to be due to them being good substitutes for humans. They also ‘physicalise’ the human wish for transcendence (Bloch p.5 above) in Gersht’s film by keeping the memory of those who died alive in the minds of the living. But in Gell’s terms this film can be seen as enchanting the viewer with beautiful and sublime images of the forest but without explicitly referring to what the artist is representing. There is a, ‘certain indecipherability’ in this work, like Gersht’s blurred photographs of the Ukraine forest landscape from a train (figs. 7&8).

Fig 7. Ori Gersht Gallicia 2005 C-Type print

Fig 8. Ori Gersht. Drawing Past. 2005. C-Type print

Finally, environmental concerns were held by Joseph Beuys (b.Germany 1921-1986) particularly in his work 7000 Oaks (fig 9), which he began in 1982 in Kassel, Germany. 7000 oaks (or social sculptures) were planted around the city (and in Manhattan) each with a basalt marker by it side to represent the earth’s ancient energy and show the permanent state of flux in which all life exist. Beuys was no ordinary sculptor but he was also a shaman, a teacher, a performance artists and a debater. In this ongoing work (as the trees are still growing) he intended to generate an ‘ecological awakening’ for mankind, as part of his mission to initiate environmental and social change through art.

Fig 9 Joseph Beuys part of 7000 Eichen (7000 Oaks) 1982-1998

basalt marker and red oak tree

Here the tree is not symbolizing death, or nation as in the examples above but is a practical goal of reforestation for Beuys who founded the Green Party in Germany. The symbolic aspect in this example is not the trees themselves but rather in Beuy’s concept of the artist as a shaman. This would fit Gell’s notion of art as a system of action, intended to change the world, rather than the work of Gallacio or Gersht who symbolise or reflect on past or present events with their use of trees and are not attempting creating social change.

Conclusion

The category ‘tree’ has been considered a cultural and historical construct and is used symbolically and metaphorically cross-culturally and in contemporary art. In this essay I have reviewed some of the theories relating to trees in anthropology in order to approach a study of the use of trees in contemporary Western art. I would argue that some artists reference trees, the primeval natural object, in order to anchor or root our sometime precarious feelings about the world we inhabit today. Some, like Gallaccio, use natural materials to show temporality and change and perhaps a renewal of proximity to nature. Other, like Gersht, used tree imagery in their work on memory, and others still, Beuys included, focus on loss of nature in the age of technical reproduction and on natures comprehensive destruction. Artists want their work to be seen, thought about and absorbed and by using trees in their practice they not only reference art history but use a universal category that most people can relate to even if the artist’s precise intentions are not fully understood. Also the places where these works using/representing trees are normally found are art museums, galleries and fairs so I have used an example of Beuys’ work to show how such concerns can escape the confines of the gallery and aim towards social or environmental change, which Alfred Gell considered to be the aim of art as a system.

As a postscript since finishing this essay I would like to mention an exhibition that has just finished at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris by a young French artist, Loris Gréaud. One room contained an installation of black trees coated in gunpowder (Fig 10). I am not sure of the artist’s intention here as it ‘displays a certain cognitive indecipherability’ (Gell above) but at the end of the room, beyond the trees, is a screen or ‘Film for the void’ which switches itself off if anyone approaches. One wonders if anything is showing on the screen when nobody is there? This calls to mind, as mentioned above, ‘If a tree falls in the woods and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound? And it is just one more example of the use of trees in Western art today.

Fig 10. Loris Greaud Gunpowder Trees.

From the Celar Door 2008

Exhibition images at Gimpel Fils Gallery

London 2007

‘Wood for the Trees and Falling Leaves’

Including curator’s (Alice Correia) description of each work from www.gimpelfils.com.

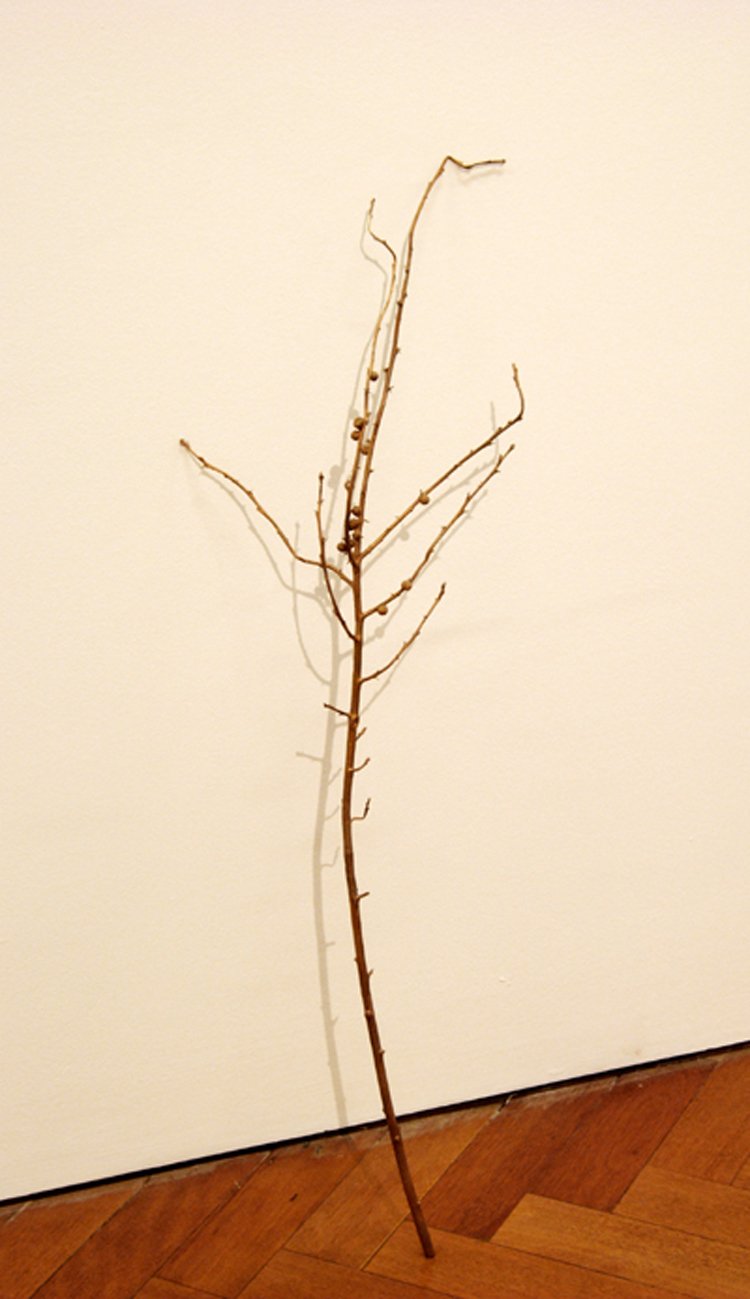

Anya Gallaccio the feelings gone and I just can’t get it back 2006

bronze cast ilex twig. 88 x 24 x 14 cm

Gallaccio’s work has been concerned with constant change and effects of time. In recent bronze sculptures she has halted time, challenging our perceptions of natural materials.

Alex Antes Structure for Birds 2006. Pencil on paper. 200 x 200 cm

Alex Antas is attempting to slow down the process of looking by creating faint and delicate pencil drawings. His imagery is an investigation into the meeting of urban and a natural landscape.

Blaise Drummond Words of Wisdom. 2006 162 x 200cm. oil and sepia ink on canvas

Juxtaposing trees with images of high modernist architecture Blaise Drummond celebrates the natural world and its relationship to modern culture in his painted and collaged canvases. His work retains a hope in nature amid human constructions of progress.

Alex Hutte

Photographing the reflections of trees in the water,

Alex Hütte’s images contemplate the true nature of representation.

Natural forms become indistinct, while figures stand waiting to

Christopher Stewart. C-Type photograph 2003 Geramny.

Christopher Stewart’s photographic work also shows us the strange duality of fear and beauty. The work included in this exhibition depicts a forest watchtower, reminding us of Foucault’s theory of the panopticon, where visibility is a trap.

Clare Woods Hanging Head 2007

Enamel and oil on aluminium. 132.1 x 5cm.

Trees, stumps and canopy are depicted in fluid glossy paint by Claire Woods combining both attractive forms and eerie mystery. Her work demonstrates a fascination with the supernatural and the unseen presences.

Hannah Maybank The Collective 2006. Acrylic and latex on canvas. 165 x 228.5 cm.

Hannah Maybank uses the tree motif as a tool to explore ideas of evolution, time and dissolution. Her layered paintings become three-dimensional objects as swaiths of paint peel away from the surface.

Henna Nadeem from a Picture Book of Britain. Digital print

Hannah Nadeem’s digital prints combine found photographic imagery with patterns from non-western sources. In her work the British countryside and the decorative motif are grafted together as a reflection on identity and belonging.

Jost Münster Crossroad

Jost Münster combines images of trees, roads and blocks of colour to create imaginary landscapes. Using the special environments and the visual motifs of his urban surroundings he investigates the relations between colour, form and shape.

Michelle Dovey Sunset Trees (after Wouwermans) 2006. Oil on canvas. 30.5 x 40.6 cm.

Working from eighteenth century paintings by Stubbs and Constable, Michelle Dovey gives prominence to the pictorial components often overlooked in art. Instead of being props or framing devices trees are joyously moved to the centre of her convases.

Neeta Madahar Falling 2005

Neeta Madahar’s film Falling in which sycamore seeds tumble slowly toward the viewer. In its tranquillity, the film evokes the passage of time and the processes of change, which also holds the promise of regeneration.

Nogah Engler Three Ways II (1,4,&5) 2006. Oil on board. Triptych, each 30 cm diameter.

At first Nogah Engler’s snowy landscape paintings appear uncomplicated, however, closer examination reveals disturbing details. Engler’s forests include dead deer, watchtowers and nooses hanging from the tree branches evoking the places in the Ukraine where her father and grandfather hid during World War II.

Rory Macbeth from the series Wood for the Trees 2006

Rory Macbeth’s hand carves trees evoke the spirit of Robert Smithson. Sculpted from real trees, following the curve of their branches, Macbeth’s trees become art objects, at once representations of trees and trees in themselves simultaneously.

My Interview (extract of) Curator, Alice Correia. April 2008.

LB What were the main reasons for your gallery curating a show such as Wood for the Trees?

AC The main reason was my personal interest in trees, which came out of my PhD research into Anya Gallaccio's "Beat" exhibition/ Duveen Sculpture commission at Tate Britain. It appeared to me that despite the fact that trees were apparently un-fashionable subjects in art during the 1990s (with ref to Brit pop, Hirst, Lucas etc) there was/ is an increasing number of artists who were looking at trees today, either because of current environmental issues or who were re-examining the art historical preoccupation with trees.

LB Which came first, the amount of artists you knew who used/represented trees, or the idea for the show first - then artists were found?

AC It was a bit of both. I knew of some artists who used trees and thought that the subject would make for an interesting show. When the possibility of actually curating the show arose I then undertook further research to find additional artists to approach.

LB. How much interest did this exhibition create with the pubic compared to other shows?

AC Difficult to tell- do you mean other shows at Gimpel Fils, or other shows that were on at the same time in different galleries? In terms of the exhibition in comparison to other GF shows, I think it did quite well. It was reviewed in Time Out and was featured in some of the London based newspapers. We certainly had good visitor attendance and I suppose I could argue that that the fact that someone like you is contacting me about it over a year since its display demonstrates that it has had a lasting resonance.

LB Were commercial concerns more paramount in this exhibition than others?

AC Commercial concerns are generally less important when curating a group show than a solo exhibition of an artist the gallery represents

Fractured Images of Trees in Modern Art

Fig 11. Pablo Picasso. Landscape, La Rue-des-Bois. 1908. 291/4 x 24 ins

Fig 12. Fernand Léger. The Level Crossing. 1912. 37 x 32 ins

Fig 13. Piet Mondrian. Composition No. XV1 (Composition 1 Trees). 1912/13. 33 1/2 x 29 1/2 ins.

Fig 14. Paul Klee. Deep in the Forest. 1939. 20 x 17 ¼ ins.

Examples of contemporary artists using trees or tree imagery in their work.

Fig.15. Andy Goldsworthy. Stacked Oak 2007. branches left over from trees being felled.

Fig 16 Andy Goldsworthy Hanging Trees 2006. Oxley Bank

Fig 17. Abbas Kiarostami Trees in Snow 1978-2003 photographic prints.

Fig 18. Mike Marshall A Place Not Far From Here 2005 video projection with sound DVD, 5min 40 secs

Fig 19. Rodney Graham. Napoleon Tree 2003.

Archival inkjet photo

Fig 20. Tim Hawkins. Rootball 1999. paper, glue and string.

Fig 21. Philippa Lawrence Bound 2006 dead trees wrapped in bandages

Fig 22. George Baselitz. The Tree 1966. oil on canvas

Fig 23. Giuseppe Penone. Tree of 12 Meters 1980-2. wood

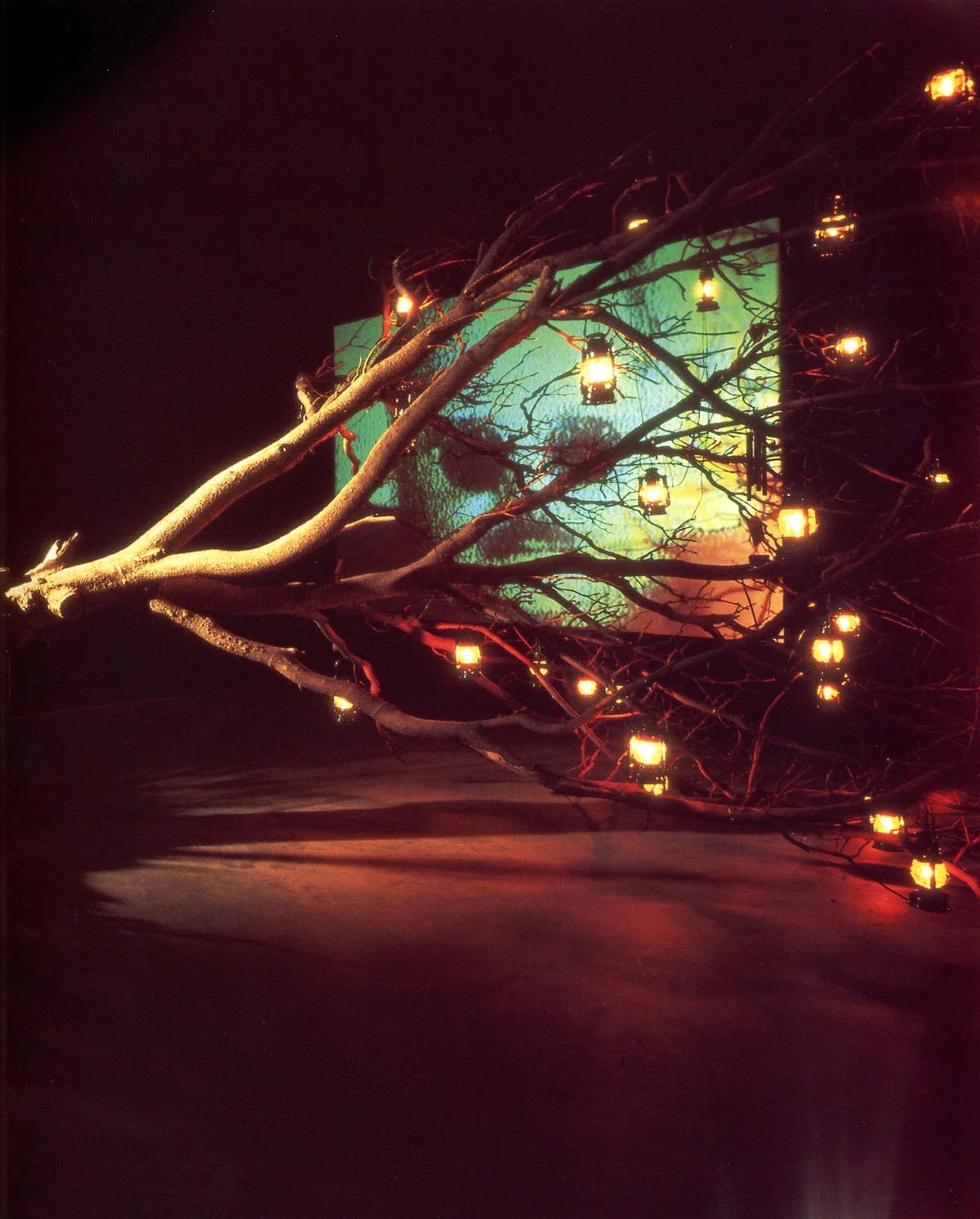

Fig. 24. Hamish Fulton. Untitled, Japan. (detail) 1996. installation

Fig. 25. Bill Viola. The Theatre of Memory(detail) 1985. tree, lanterns, video

List of Illustrations

Essay

1. Casper David Friedrich, Oak Tree in the Snow 1829. In The Magic of Trees Foundation Beyeler. P.6.

2. Anya Gallaccio, Beat. 2002. In Beat Tate. p.25.

3. Anya Gallaccio, blessed 1999. In Beat Tate. p.39.

4. Anya Gallaccio, because nothing has changed 2000. In Beat Tate. p.39.

5. Anya Gallaccio, preserve ‘beauty’ 1991. In Beat Tate. p.41.

6. Ori Gersht, Forest 2005 In The Clearing Ori Gersht Film and Video Umbrella p. 85.

7. Ori Gersht, Galicia 2005 In The Clearing Ori Gersht Film and Video Umbrella p. 25.

8. Ori Gersht, Drawing Past 2005 In The Clearing Film and Video Umbrella p. 51.

9. Joseph Beuys 7000 Eichen 1982-1987/1998 http://www.middlebury.edu/arts/capp/artists/beuys.htm

10. Loris Gréaud The Cellar Door 2008 Time Out Magazine Ltd April 24-30 2008 p.66.

‘Wood for the Trees’ exhibition

Images of various artworks from Wood for the Trees and Falling Leaves exhibition.

Gimpel Fils. 2007 http://www.gimpelfils.com/print/p_exhib_works.php?exhib_id=72

Fractured Trees

11. Pablo Picasso Landscape, La Rue-des-Bois 1908 In The Magic of Trees Foundation Beyeler. P.41.

12. Fernand Léger The Level Crossing 1912 In The Magic of Trees Foundation Beyeler. P.43.

13. Piet Mondrian Composition No.XV1 (Composition Trees) 1912. In The Magic of Trees Foundation Beyeler. P.51.

14. Paul Klee Deep in the Forest 1939 In The Magic of Trees Foundation Beyeler. P.83.

Contemporary artists using trees.

15. Andy Goldsworthy Stacked Oak 2007. In Andy Goldsworthy at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park

Yorkshire Sculpture Park p. 89.

16. Andy Goldsworthy Hanging trees 2006. In Andy Goldsworthy at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park

Yorkshire Sculpture Park p. 146.

17. Abbas Kiasostami Trees in Snow 1978-2003 Victoria and Albert Museum

http://www,vam.ac.uk/collections/photography/past_exhns/abbas_kiarostami/index.html

18. Mike Marshall A Place No Far From Here 2005 Mike Marshall Ikon Gallery p.42.

19. Rodney Graham Napoleon Tree 2003 http://www.artists4kids.com/artists/graham.php

20. Tim Hawkins Rootball 1999 The Greenhouse Effect Serpentine Gallery p.4.

21. Philippa Lawrence Bound 2006 http://www.philippalawrence.com/f/p_bound.html

22. George Baselitz The Tree 1966 In The Magic of Trees Foundation Beyeler. P.104.

23. Giuseppe Penone Tree of 12 Meters Tate Modern the handbook Tate p.211.

24. Hamish Fulton Untitled, Japan 1996 In The Magic of Trees Foundation Beyeler. P.124-5.

25. Bill Viola Theatre of Memory 1985 In The Magic of Trees Foundation Beyeler. P.128-9.

Bibliography

Bloch, Maurice ( 1998, 2005) Why Trees, Too, Are Good to Think With: Toward an Anthropology of the Meaning of Life in The Social Life of Trees, Laura Rival (ed) pp.39-55. (1999) Berg. also in Essays on Cultural Transmission Maurice Bloch (eds) pp. 21-38. (2005) Berg.

Bloch, Maurice (2005) Where did Anthropology Go in Essays on Cultural Transmission. Maurice Bloch (eds) pp. 1-19. (2005) Berg.

Bode, Steven (2005) Tracks in the Forest, in The Clearing: Ori Gersht. Steven Bode and Jeremy Millar (ed) pp.5-6. Film and Video Umbrella

Deuchar, Stephen (2002) Forward in Beat, exhibition catalogue. Tate.

Gallaccio, Anya (2002) Beat, exhibition catalogue. Tate.

Garner, Andrew (2004) Living History: Trees and Metphores of Identity in an English Forest. in Journal of Material Culture 2004; 9; pp. 87-100.

Gell, Alfred (1998) Art and Agency Oxford University Press.

Hohl, Reinhold (1999) Pictures about Trees in The Magic of Trees exhibition catalogue. Foundation Beyeler (ed) p.9-20. Verlag Gerd Hatje.

Millar, Jeremy (2005) Speak, You Also, in The Clearing: Ori Gersht. Steven Bode and Jeremy Millar (ed) pp.9-19. Film and Video Umbrella.

Rival, Laura (1998) Trees, from Symbols of Life and Regeneration to Political Artefacts. in The Social Life of Trees, Laura Rival (eds) pp. 1-36. Berg.

Seeland, Klaus (1997) Nature is Culture: Indigenous Knowledge and Socio-Cultural Aspects of Trees and Forests in non-European Cultures. ITDG Publishing.

Thomas, Nicholas (1998). Forward, in Art and Agency Oxford University Press.

Thomas, Nicholas (2001) Introduction, in Beyond Aesthetics: Art and the Technologies Enchantment. Christopher Pinney and Nicholas Thomas (eds) pp. 1-12. Berg.

Turner, Victor (1967) The Forest of Symbols Ithaca: Cornell University Press.